Victoria Falls, on the border of Zimbabwe and Zambia, made headlines at the end of 2019 with images of an almost entirely dried up rock face. The Zambezi River had allegedly dried up due to climate change. This is not the case. Today, thousands of liters of water rumble off of the cliffs every second. How could this misunderstanding arise? Let’s find out.

Victoria Falls: dry?

It is November 30, 2019 when the first news reports surface in Australia about naked cliffs and a dried up Victoria Falls. In the following days, this headline and a video of the scene spread around the world via, among others, The Guardian, Reuters and Algemeen Dagblad. Zambia’s President Edgar Lungu tweets about the images: “This is a powerful reminder of what climate change is doing to our environment.”

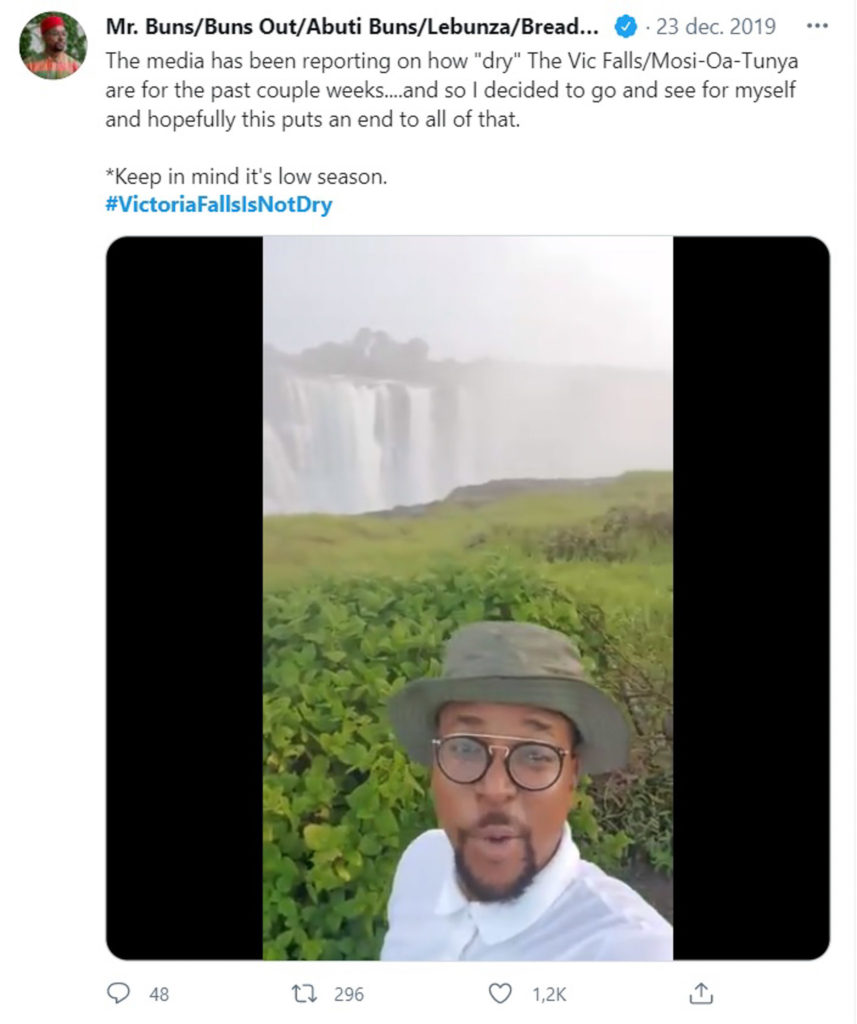

The community around the waterfall is challenging the posts on twitter with #VictoriaFallsIsNotDry. Under that hashtag, it is suggested that the high and low seasons are the cause of dry cliffs. In addition, the photos and video were taken at the Eastern Cataracts of the fall. This would give a distorted view, since the waterfall is more than a mile wide.

Records are being broken

The water flow on the Zambezi is monitored and controlled by the Zambezi River Authority (ZRA). Their data shows that water levels at the Victoria Falls monitoring station are always at their lowest between October and January. The current is highest in the months from February to June. Depending on the season, it can be predicted whether more or less water falls from the Falls.

What has been reported less in the media is that, five months after the dry cliffs, a record amount of water rumbles from Victoria Falls: 4,289 cubic meters of water per second. That’s equivalent to 103 Olympic swimming pools per minute. This year, the waterfall seems to break those records yet again, with a higher water volume already in the last month than last year.

Despite these record amounts of water, the majority of tourists at the waterfall are convinced that Victoria Falls is a last chance tourism destination. Research from 2019 and 2020 shows that seventy percent of tourists expect the waterfall to dry up in the future. Thirty-eight percent of those same respondents would not want to visit the site again once the water is gone.

El Niño is guilty

The waterfall turned into the dry cliffs as a result of El Niño, a weather pattern that disrupted annual rainfall in southern Africa. An El Niño is a large-scale warming of seawater in the Pacific Ocean that shifts rain areas from land to sea. As a result, exceptionally little rain fell in Africa. Namibia and Zimbabwe, among others, declared a state of emergency because of the shortage of water and food. This extreme drought and lack of rain caused the bare rocks of Victoria Falls which took the media by storm.

It is true that the dry cliffs are in themselves seasonal and unrelated to climate change. Extreme droughts, on the other hand, can be linked to climate change. Scientists see a correlation between global warming and more frequent droughts in southern Africa. This could mean that Victoria Falls in the low seasons is more likely to be as dry as at the end of 2019. In addition, academic research shows that the temperature in Livingstone – the town on the waterfall in Zambia – has risen consistently by slightly more than one degree over the past 40 years.

In conclusion, global warming is driving changes at Victoria Falls. No, the waterfall or the river are not drying up, nor will it eventually dry up. But extreme droughts are becoming more common, which in turn will make the waterfall drier from time to time.

Recent Comments